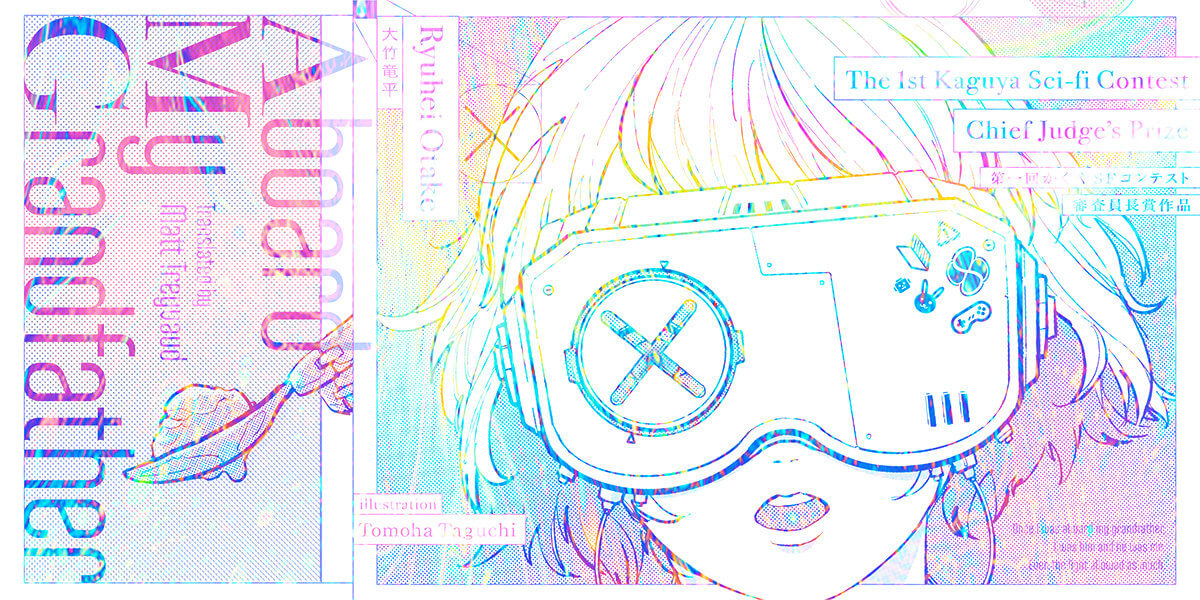

Kaguya Sci-Fi Contest, chief judge prize winning story

Illustration: Tomoha Taguchi / Cover Design: Ryuhei Otake

Once I was aboard my grandfather, I was him and he was me. Even the light allowed as much.

The whole thing was my grandfather’s idea. What he wanted was to somehow get my body to school. He could have fitted an engine to my bed and rammed it through the classroom door, or built a school from blocks of smooth quartz in virtual space and taken me there. But he didn’t even try those ideas. He was too clever. And too crazy.

First, he removed his eyeballs and replaced them with high-performance lenses. Then he pierced his ageing ears and donned a pair of parabolic reflector earrings. He swapped his brittle bones for a ceramic frame, and worked on his legs until he could have carried a refrigerator on his back. To keep his organs from squirting out under the heavy load, he covered his body in tough fiber. When he was done, he looked more like a man of papier-mâché than of steel, but definitely too high-powered to be called elderly. It was a little easier to understand when I thought of him as a folk craft made of components from a gaming PC.

The great man stood at the foot of my bed, hands on hips. I looked up at him meekly.

“It’s not healthy just playing video games all day.”

His voice made the air in my sickroom ripple like a theremin.

He handed me a gigantic pair of goggles and two wire-veined gloves. I put them on without a word. Through the goggles I saw a pale invalid sitting on a bed—in other words, me. My grandfather being absent from the scene, it was only natural for the me on the bed to address me instead.

“Can I go to school like this?”

My head nodded.

“They gave permission for you to attend.”

It was strange to hear my grandfather’s voice come from my mouth.

And that was that. From this day on I would be my grandfather’s pilot, with my sickroom as cockpit. The unpleasant feel of the gloves on my hands was of a piece with the tremors in his once-knotty fingers of steel; the surprising lightness of the goggles echoed the vulnerability of his bald crown. I took a few clanking, experimental steps, circling myself where I lay on the bed, mouth hanging open vacantly beneath the iridescent goggles. I felt my grandfather’s silent laughter in the movements of our facial muscles.

※

Real school was nothing like the buildings in video games. All the materials were rendered in high definition, and when someone damaged a wall it didn’t reload. For someone like me, who knew nothing outside the walls of my sickroom except what I saw on my screen, it was too much information to digest. I could only marvel like a prisoner released from a dungeon. So this is the outside world! Instead of flat images on a display, I had classmates who roamed the building in three dimensions without worrying about ping rates. Doors opened in the walls automatically, and railings linked to countless classrooms conveyed students to their destinations. Apparently this was how schools were supposed to be.

When our body glided into a classroom, the other students all turned their heads toward us in shock. I gestured reassuringly: Don’t worry. I’m not some weirdo. The students backed away, crowding into the corners of the room. Maybe I got the gesture wrong.

“I’m Asahina Hikasa.”

My self-introduction, delivered in my own voice, met with scattered applause. I glanced at the fierce profile of the 2.5-dimensional teacher on the wall monitor. There were no seat assignments, apparently, so I found a desk and sat down for class. Japanese, Math, Science, Future Studies. Epidemiology, Anthropology, Online Communication. I had studied all the same things in my sickbed.

Real class was full of noise. It all bothered me. Slippers dragging on the floor. The swaying cowlick of the student in front of me. Implants chirping with incoming messages. And someone, somewhere, was secretly eating their lunch early. Getting an education in a place like this seemed like a superhuman feat. I felt sincere admiration for the students who managed it.

My grandfather seemed to be suffering from back-to-school jitters after his fifty-year absence. Our fingers trembled, tapping the wrong things on the tablet. After one question from the teacher to the class, we accidentally hit the virtual “raise hand” button. The teacher called on me for the answer.

The students watched quietly as I approached the podium up front. It seemed like they were starting to get used to me. Or maybe they were just intimidated by this bizarre old coot in their midst.

I wrote the answer directly on the wall monitor with my finger. The screen was soft and springy. How hard was I supposed to press? I wasn’t sure, but it felt designed for normal human hands to write on. Turning a simple equation into an exercise in calligraphy seemed pointless, but that was how things were done here. The students were proud of their healthy bodies and made full use of them to answer questions. I decided to show off our strengths, too, and bore down harder on the monitor.

Naturally, my finger punched right through it. There was a flash of yellow as the screen tore.

The students showered me with applause. The furious teacher yelled that class was cancelled. My grandfather and I smiled awkwardly.

At lunch, a constant stream of classmates dropped by to say hello. I didn’t know how to respond. Offline communication had never been a required subject for me. Some of the students timidly touched my grandfather’s body. Some praised me for ruining class. Some observed me from afar. Some recorded me. Some took my measurements. I used lulls in the conversations to cram the lunch my grandfather had packed into his mouth. After my crowd visitors dwindled away, one last student came to talk to me: Tamaki.

Tamaki had an attractive face. At least, I thought so. Large, expressive features framed by black hair with a tinge of purple. Even through my grandfather’s eyeballs, I found the effect appealing. Loud voice. Tall and healthy, with long, sturdy limbs and a different kind of toughness to my grandfather’s. For a moment, I imagined Tamaki lying on my bed, head and feet dangling over the ends. It was a little unnerving to think we could be so different at the same age.

Tamaki was the first one to ask my grandfather’s name. Mitsuo, I said. Tamaki smiled and waved at my grandfather like a wind-up toy. “Does Mitsuo like sweets?”

But then the bell rang. Before I could answer, Tamaki sat back down. Lunch had passed twice as quickly as class.

I didn’t yet understand that I had just been invited to hang out after school.

※

At the end of our uneventful (I hoped) first day of school, we were just putting our outdoor shoes back on when Tamaki ran up with an urgent question: ice cream or ramen? Ice cream, I said. That would be easier to get into my grandfather’s mouth.

Apparently, it had rained while we were in class. The plastic road had a bluish glow. Even the filthy air of the industrial zone felt more bearable now that the raindrops had washed it clean. But it also felt as if my grandfather’s tread was simply lighter than it had been this morning. I wondered if Tamaki came this way often. Our conversation was light but unflagging as I followed my classmate through the maze of streets.

It was finally dawning on me: “After school” was essentially a period of untracked motion from school building to bed. The goal was fixed, but you had boundless freedom to fold and refract the route. We stopped at vending machines, hopped over puddles, gave food to the ashy cats in the rubble. Strings of random events like this were entirely new to me. All I had ever done before was eat the food I was given, in the order in which it arrived, and take my medicine at the prescribed times. The lights went out before I was sleepy; every morning, I woke up in the same sickroom. I didn’t think of this as being robbed of my freedom. I just wasn’t able to innocently refract the course of my life like some could. I never cursed my feeble body, although some nights I dreamed of a perfect one. This was the source of my grandfather’s madness.

※

“Doesn’t Mitsuo talk?” Tamaki asked, from the other side of a gigantic sundae and a bowl of matcha ice cream.

“Now that you mention it, he isn’t talking today.”

My grandfather and I scooped up a spoonful of green ice cream where it was melting and put it into our mouth. Tamaki went on silently demolishing a tower of cream, despite not seeming especially interested in it.

My grandfather had been keeping quiet for my sake. I knew that. He wanted to grant me a tougher body, not the aphorisms of an elder. I just had to concentrate on carefully shoveling matcha ice cream (his favorite) into our mouth.

My grandfather’s self-modifications were far beyond what modern medical science or engineering would permit. In all likelihood, this would be our first and last joint endeavor. The world was full of housebound kids like me, but my grandfather was one of a kind. I would never again lament the age I had been born into. The present. Reality. This very moment—where was it, really? In the texture of crisp, clean sheets? The twilight flowing across the dusty café seating? I couldn’t taste the sweetness of the sugar, but the green was as vivid in my eyes as it was in my grandfather’s.

I shook off my reverie to see Tamaki looking at me in apparent concern. The movement of those eyelids across eyes like shimmering pools robbed me of my words. The light from the setting sun outside made Tamaki’s features seem more chiseled than ever. What did we look like to people passing by outside? An old man and his grandchild? If I had a healthy body like you, I would wear a uniform, too, and worry about wrinkling my skirt when I sat. I didn’t say this, of course. Instead, I blurted out a question about what I could see through the window.

“Why do you think that puddle shines like a rainbow?” I asked, pointing through the glass.

Tamaki laughed. “Is that what you were thinking about? For the same reason that soap bubbles shine, right? I know that much. Not that they teach that stuff in class. That’s why I always take the long way home.”

For some reason, I felt a deep gratitude. I knew it was hopeless to try to express it, but I had to say something. Our mouth opened.

“When the sun’s rays hit the surface of the oil, the light splits into two. The two waves interfere with each other based on the optical path difference. That creates the iridescence you see.”

That was the last time I heard my grandfather’s voice.

The image in my eyes bled into the image in my grandfather’s. Light can only interact with itself, and the same was true of my grandfather and me. We could never inhabit exactly the same time or place. We would never see the same pattern of iridescence. But at that moment, looking in the same direction, we both saw the same seven colors shine.

1st Kaguya Sci-Fi Contest Grand Prize Winner

Dewdrops and Pearls by Umiyuri Katsuyama, translated by Eli K.P. William