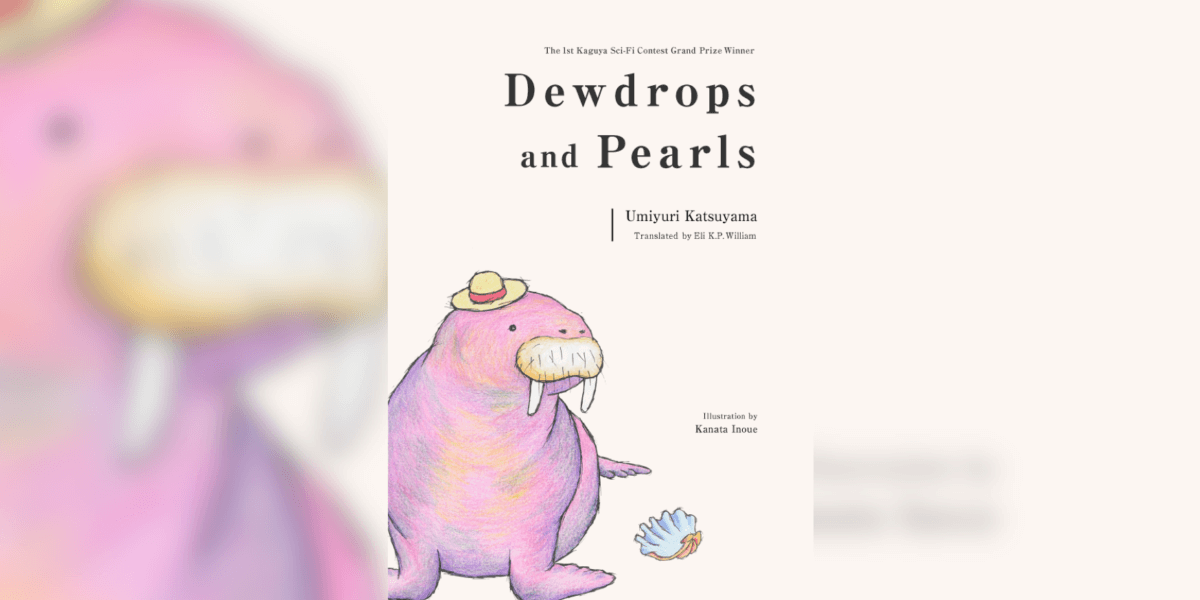

Kaguya Sci-Fi Contest, grand prize winning story

My classmate, Sekiseki, was a hippocamp. Some people call them “horses of the sea,” but hippocamps aren’t actually as horsey as you might think. They have two stubby front legs, no hind legs, and a trunk that tapers from the waist to a flipper at the tip. Sekiseki was huge but could she ever swim.

The teachers told us that everyone who attended our school was a student like anyone else, whatever kind of person they were, and I had no complaints about studying with a hippocamp. Actually, it was wonderful having Sekiseki to keep me company in class. I mean, she was an amazing student. When the teachers lectured, she listened quietly, and when they posed questions, she would actually answer. The voice that came from her voice projector was a booming baritone—could have something to do with her nice build. Nothing at all like me, always hushing up and tapping my thumbnail when I get nervous.

When we had settled in after our first few days of school, I turned to Sekiseki during a class break and said, “I bet school would be fun if I could study like you.”

“Anyone want to try some?” she asked, popping a bag of peeled frozen shellfish.

“Thanks but I’ll pass,” I replied, holding up my palms towards her, and she began to munch on her thawing niblets. Earlier, she had turned down my afternoon snack, saying it would be bad for her health. My guess is that she wanted to have some but was just being polite. Now as for why I would turn down raw shellfish… well… just because.

“I think the teachers love students like you,” said Sekiseki.

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Just because.”

“Everyone likes the dunce, is that it?”

“I never said that. You’re not stupid.”

When Sekiseki finished her shellfish, she released a puff from her air bladder with a bugle-like honk.

*

We’ve been in school for a month now. I remember listening to a wooden-recorder rendition of Bach on my tablet when Grandma said, “Only two more days till school starts. How exciting!” She then took out a white blouse and navy suspender skirt for me to wear.

The school was on the edge of town, beside the sea at the base of a cliff. It was basically a concrete box with a pale blue floor and a white cloth stretched taut over top as shelter from rain and sun. You got in by climbing from the edge down this stainless steel ladder.

When I stepped down on my first day, two women in black one-piece skirts with white collars stood waiting. They looked nearly identical, with grey hair turned more than half white. Their name tags read Ms. Midoriko and Ms. Momoko. When I gave them my name, Ms. Midoriko stamped some sort of form, and Ms. Momoko told me to take my seat.

Sekiseki arrived from the sea. The loud noise of her shaking herself dry before entering made me turn my head, and I saw her slide down a steel plate that ran diagonally from the top of a wall to the floor. While I watched in astonishment, she slopped over to me, bringing the scent of ocean spray.

“I remember when this was a swimming pool but I never went in,” she said. “Now it’s a school, huh.”

Frozen stiff with surprise, all I could do was shake my head like a bobblehead akabeko toy ox.

“Sekiseki-san, take your seat. Kunenbo-san, face the front.”

Sekiseki sat behind the desk beside me. It had no chair.

“So… your name is Kunenbo,” she said in a loud voice, though for her it was obviously meant to be soft. “Isn’t that the tangerine with a nice scent? Pretty name.”

“Thanks,” I replied, looking down shyly.

Then Ms. Momoko took her place in front of the teacher’s desk and called the class to attention.

“Hello my new students. Congratulations on being accepted into our school.”

*

I adjusted to school in no time, even though I was only there three mornings a week. I’d only ever done homeschooling before, and Sekiseki was big and scary at first, but once I got used to her we became friends and chatted about everything on our breaks.

On a rainy day about a month after school started, a boy we didn’t know called out from the top of a classroom wall.

“I heard this place is, like, a school… Can I, um, join ya?”

Startled, Sekiseki and I looked over our shoulders at him.

“Come down,” Ms. Midoriko replied calmly, stopping the lesson, and the boy climbed down the steel ladder.

He had chocolate-colored skin, and wore a faded red T-shirt, knee-length shorts, and sun-glasses that covered the top half of his face. When he passed me, I got the feeling that our eyes met for a second. Ms. Midoriko told us to study on our own and brought the boy to the other side of the partition for a discussion with Ms. Momoko.

And that was how Surinosuke become our new classmate. It was Ms. Midoriko that introduced us.

“Meet Kunenbo and Sekiseki,” she said.

“I’m Surinosuke Gondo,” said the boy. “I wear these sunglasses ’cause, like, daylight is too bright for me, so better get used to it.”

“Well you better get used to the hippocamp ,” said Sekiseki, and Surinosuke smiled bashfully.

Surinosuke was assigned Sekiseki’s desk beside me, and Sekiseki got shifted to the spot behind him. Once he was seated, Surinosuke turned around and said, “Hey, I’ve seen you in the ocean. My pa told me not to get in your way or hurt you ’cause, like, you do an important job.”

“My gratitude for your cooperation, good citizen,” said Sekiseki.

“What’s this sounding fancy all of a sudden?” I said.

“It’s a stock phrase,” she replied cooly. I’d bet this was another stock phrase, just one of those expressions that gets pre-programmed into the voice projector of a sapient hippocamp.

“So you’re actually here, studying at land school,” said Surinosuke.

“What’s so strange about that? I have a lot to learn. You and Kunenbo too, no?”

“Well… I came ’cause, like, my pa told me to. Anyway, I’m glad I got to know your name. Next time I spot you in the ocean, I can think to myself, gee, that’s Sekiseki.”

“Had your fill of chatter yet, Surinosuke?” said Ms. Midoriko. “Well then, moving on.”

The next lesson was on the Akutagawa chapter in the classic, Tale of Ise, not in outdated calligraphy but a modern reprint. We listened to Ms. Midoriko read it aloud while following along on our tablets. Here’s the gist of it. More than a millenium ago, in the Heian Period, a nobleman named Ariwara no Narihira, fell in love with high-born Takaiko and ran off with her against the wishes of her brothers. Yet Takaiko was so ignorant of the ways of the world that when she saw a dewdrop on a blade of grass she asked, in all innocence, “Is that what you call a pearl?” The star-crossed lovers spent the night in an old building, where Narihara kept watch at the door, but Takaiko was gone before morning, devoured in a single mouthful by a devil.

O that I had taught thou the folly of thy pearl and vanished like a dewdrop

“The story says devil,” Ms. Midoriko explained, “but, in fact, Takaiko’s brothers chased them down, came in through the back door, and took back their sister.”

“What a relief,” said Surinosuke, and I nodded in agreement. It was way less scary for the brothers to whisk her away.

“He had to believe she was eaten by a devil or he’d never have given up on her,” said Sekiseki. She really knows what she’s talking about, I thought, and Surinosuke looked at her impressed.

During breaktime, Sekiseki finished eating her frozen shellfish, clinked a portion of it on my desk, and said, “Here, this is for you.”

“Is this what you call a pearl?” I said, feeling as though I had become Takaiko. But when I looked closely, I saw that it actually was a pearl, a warped one about the size of a soybean.

“Thanks,” I said, “I’ll cherish it,” and put it away in the pocket of my skirt.

That was the last time I saw Sekiseki. Or Surinosuke for that matter. You see, I stopped going to school.

My job is shrouded in many secrets. I can’t even tell my friends where I go. I think Sekiseki would understand.

Sapientized animals were created so they could have us do work too dangerous for humans. I’m a chimpanzee raised by humans, and I perceive myself as a human girl. I’ve never wielded my astounding strength but I could if I had to. Since the Animal Sapientization Program infringes animal rights and the functioning of AI has surpassed natural brains, the project will draw to a close as soon as the last of us still remaining retire or pass away.

Once someone said to me, “That’s even more tragic than Laika, the clueless dog they launched into space.”

It seems that this person assumed intellect and knowledge amplify emotion, and that we would experience our misery more intensely than that Soviet dog. I pretended not to hear them. What frightens me more is lifting off for a remote destination without understanding the meaning of my job.

Grandma sealed the pearl from Sekiseki in resin and made it into a droplet-shaped pendant for me. You can’t bring many belongings onto the ship bound for Mars, but I should be able to board wearing the pendant. Even with the nylon string, it weighs less than five grams.

If I return to Earth after I finish my work on the Red Planet, I’ll probably touch down in the Pacific. Imagine if Sekiseki found me, and Surinosuke was on the boat that picks me up. It would be like a class reunion.